Hello friends,

I was recently awarded a Killam doctoral scholarship to support my pursuit of a Phd in History at University of British Columbia. This is a tremendous honor, and I’m deeply grateful for this support and the opportunities it affords me. I’m humbled to be able to learn from exceptional mentors, colleagues, and projects during my time working on my PhD.

I first began working with radiation-impacted communities as a young grad student almost fifteen years ago. In these stories of radiogenic communities I found resilience and injustice at a scale that I could not even begin to comprehend.

I do not believe that the stories of ordinary people living in radiogenic communities need to be “validated” by academics or awards: they speak to a truth held in common by radiogenic communities worldwide, and they emerge from complex and enduring systems of local knowledge that encode the history of environments and human activities in ways academics are only beginning to understand. Many of these narrators will be the first to tell you how badly health studies and robust research are needed in their communities if they are to attain the services and political change necessary to address ongoing health and environmental crisis .

I interpret the Killam award as an instance of the Academy recognizing the importance of these forms of community expertise, and the responsibility of academic institutions to work collaboratively with communities in pursuit of environmental and social justice.

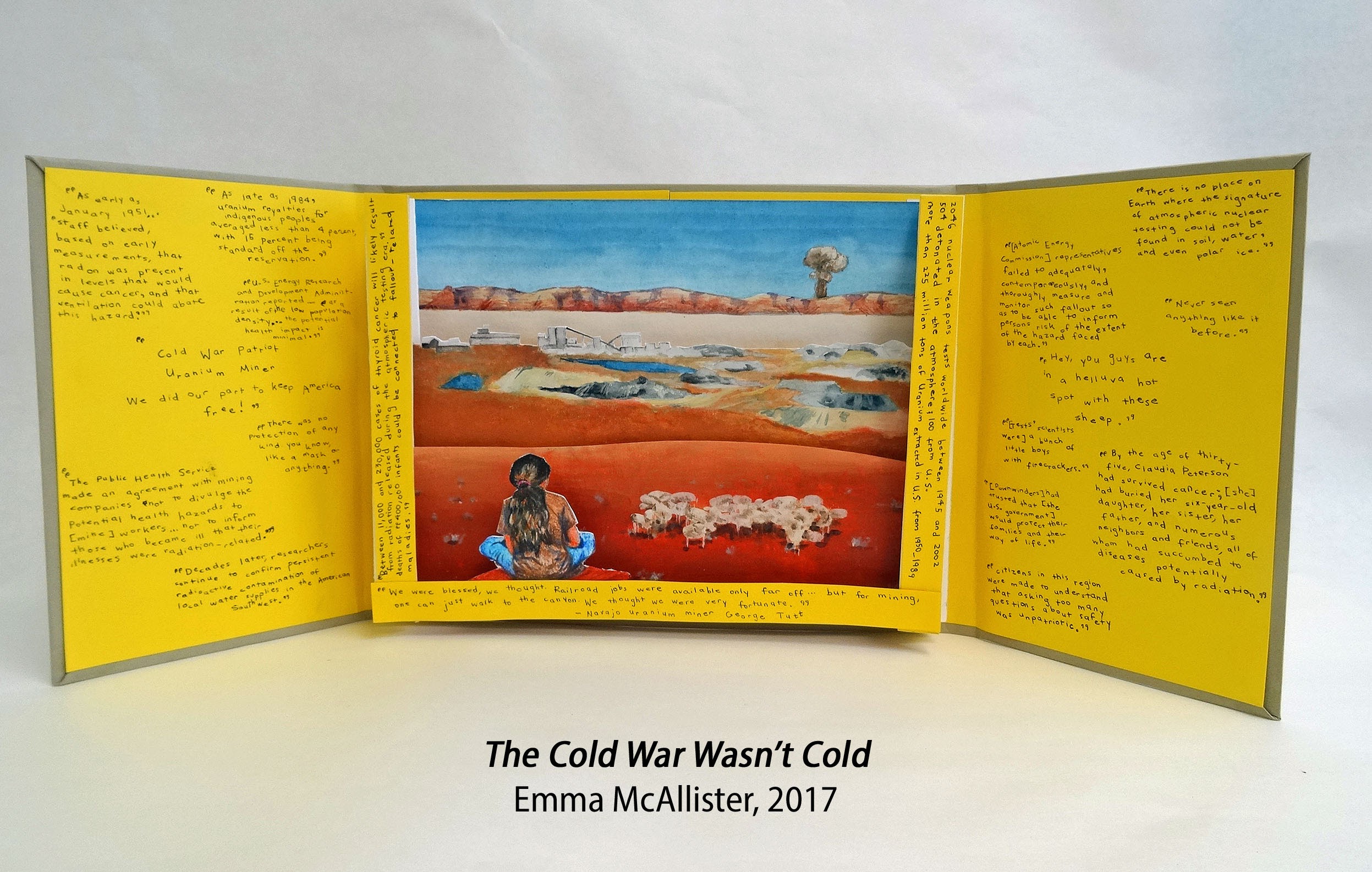

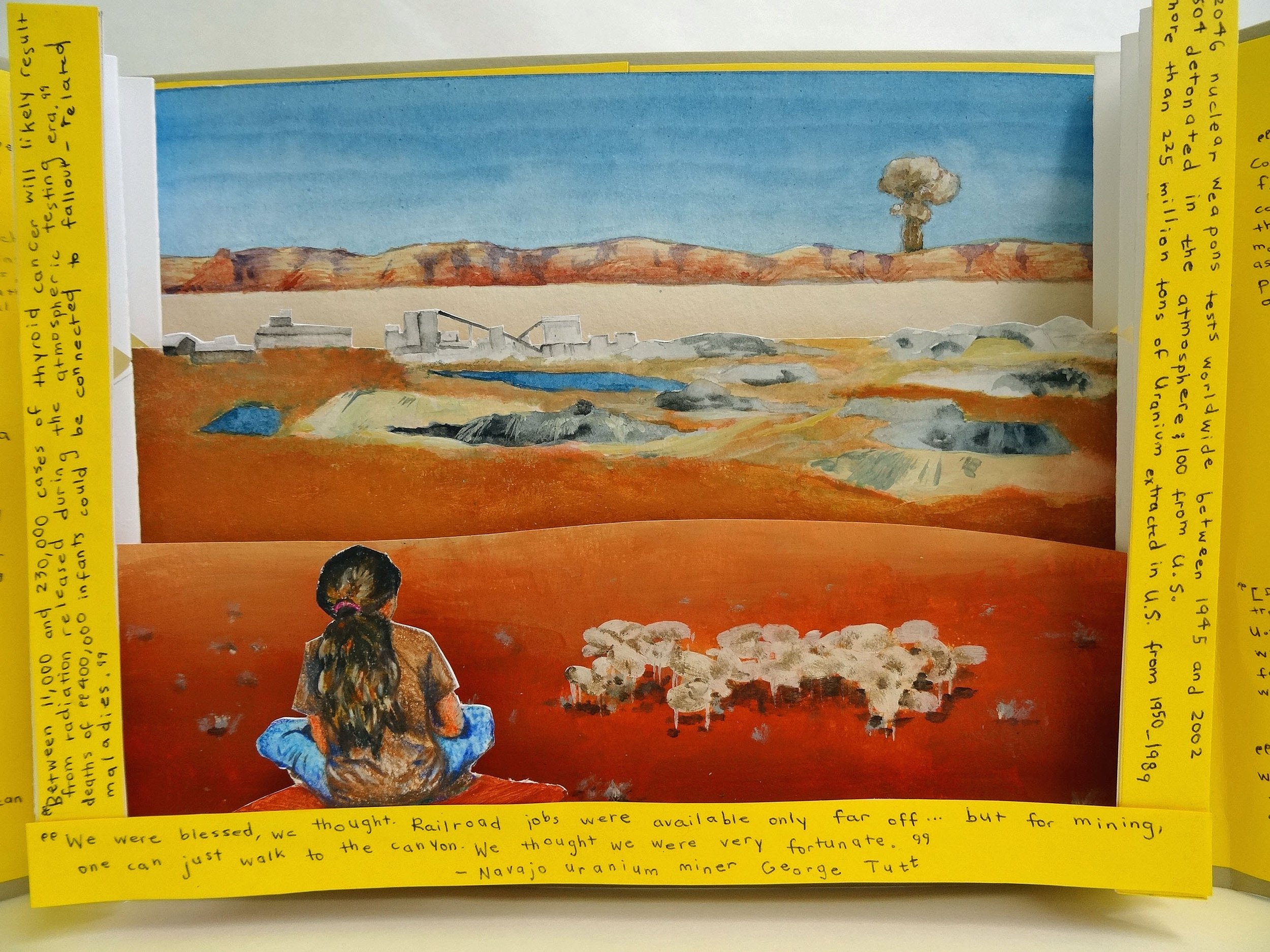

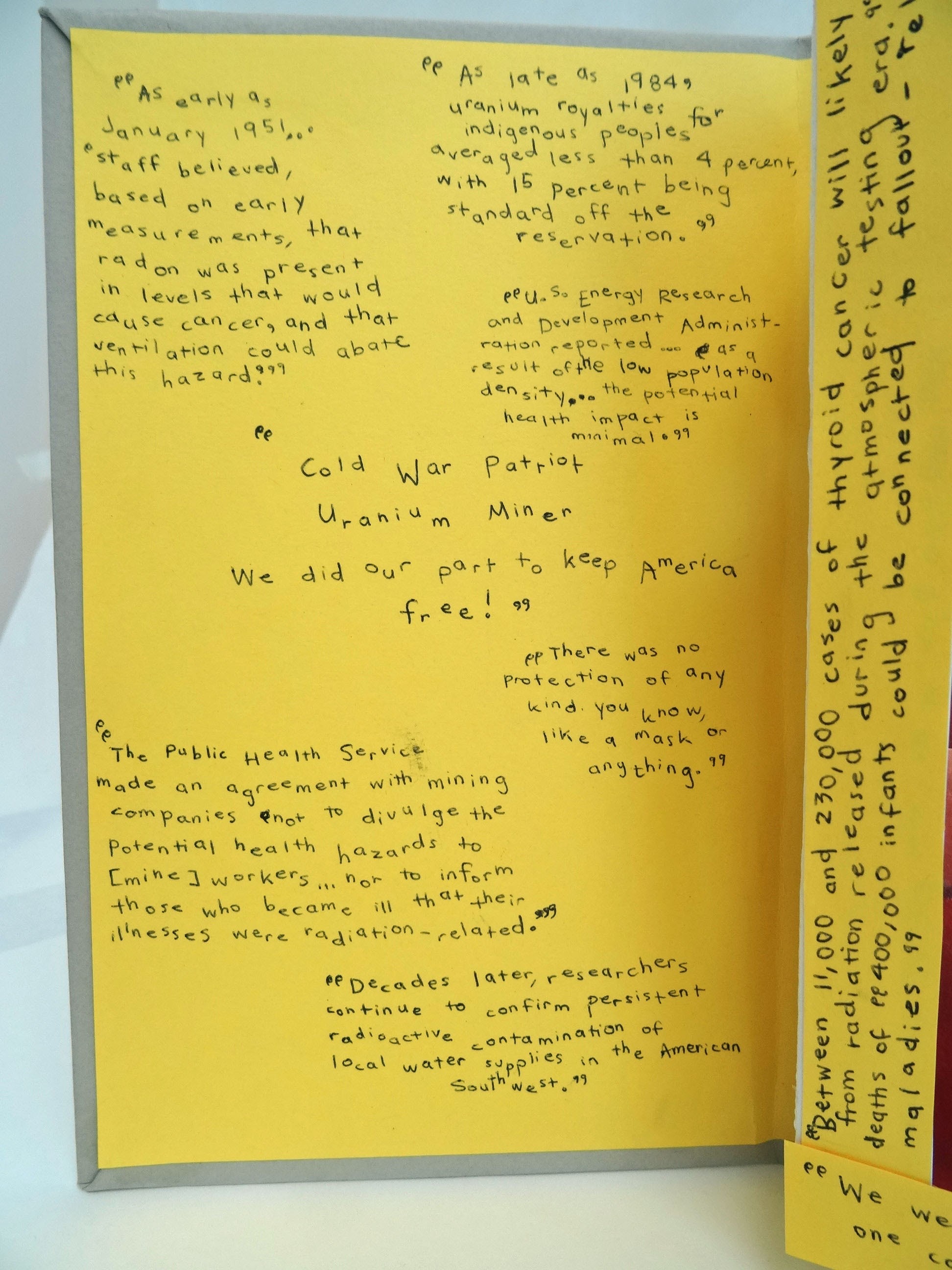

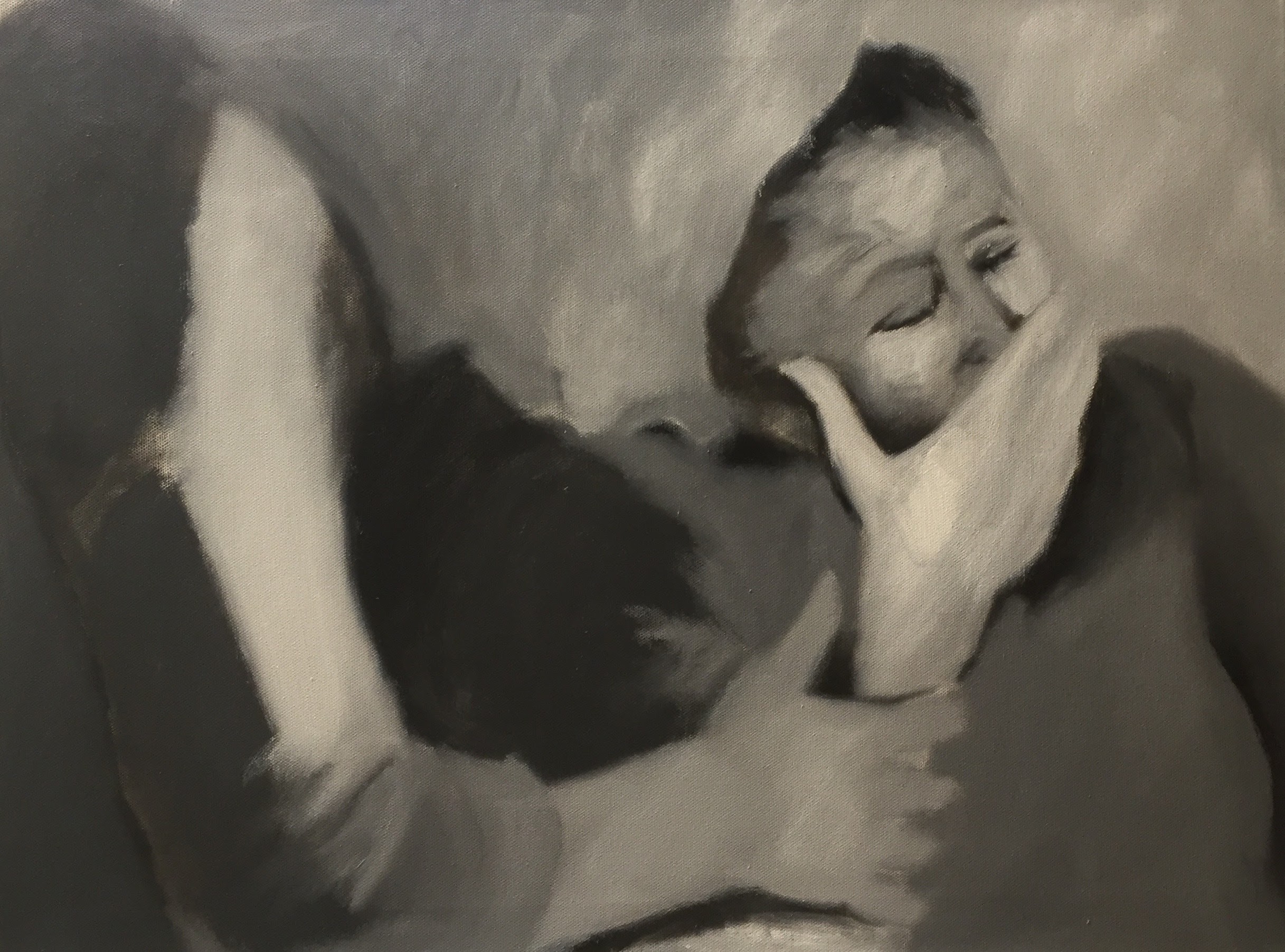

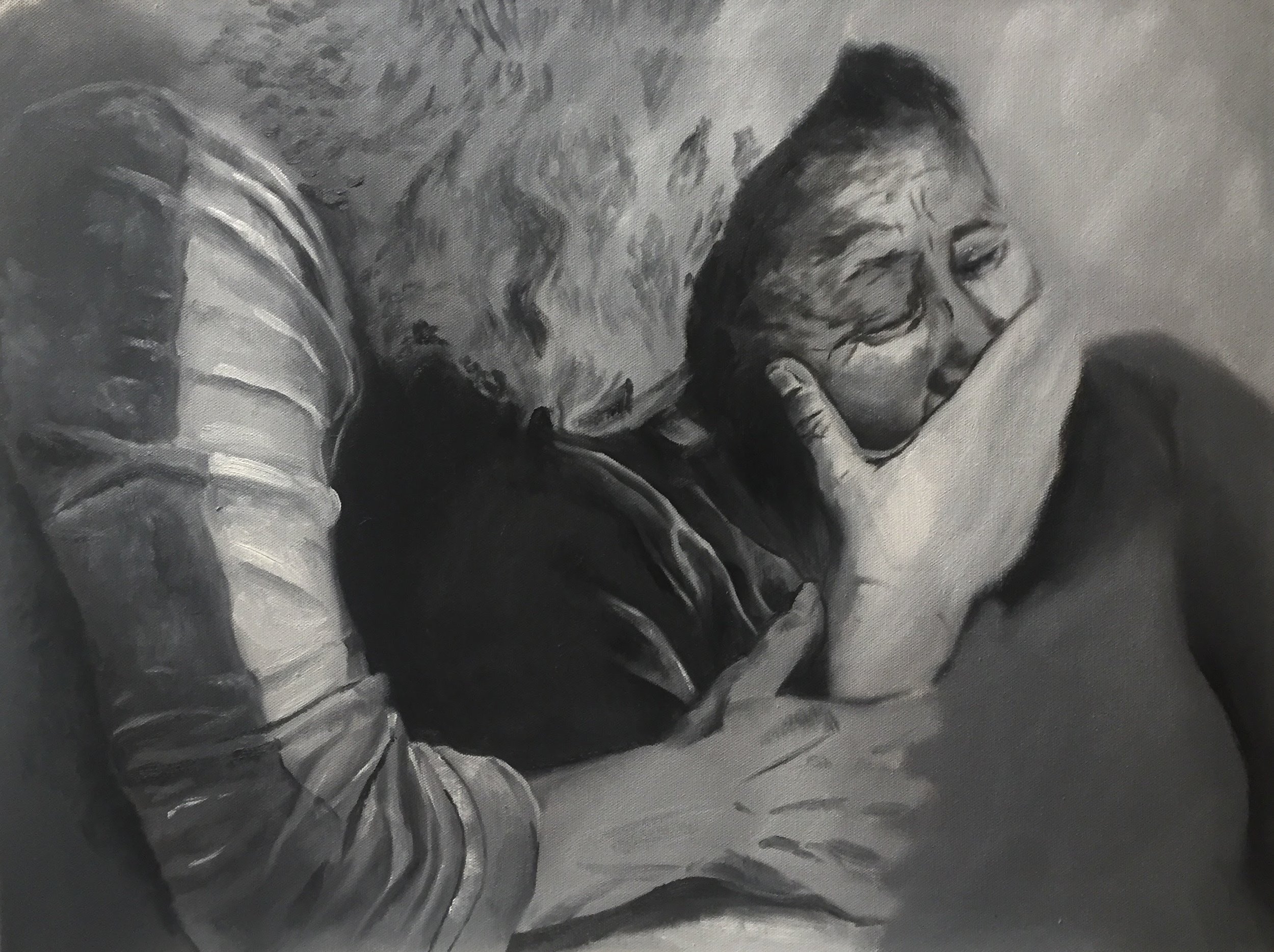

A short video was made about my research in recognition of the award, and I shared with the producers of this video some images of places, people, artwork and events that motivate my research. By virtue of this video’s format, those important people, places, and events, artworks, and stories end up getting turned into visual fragments, which does them a disservice. Please take a moment to click through some of the links in captions below to learn more about a few of the incredible activists, academics, artists, and places I’ve had the honor of learning from. If you’d like to learn more or get involved, here are some places to start.

Hanford downwinder activist Tom Bailie, Dr. Norma Field, Nagasaki hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) and activist Mitsugi Moriguchi, and Dr. Yuki Miyamoto, Richland 2018. These extraordinary activists and nuclear scholars were part of the historic Hanford-Nagasaki Bridge event, organized by the group Consequences of Radiation Exposure (CORE) and held in the Tri-Cities near the Hanford site in 2018.

Learn more:

“Nagasaki Survivor Visits Hanford, Finds Some of the Story Still Untold”

https://www.pbs.org/video/a-nagasaki-survivor-visits-hanford-gepzqn/.

Dr. Field is the editor and co-translator of Fukishima: Will you Still Say No Crime Has Been Committed. Read one of her recent works here.

Dr. Miyamoto is the author of Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima.

Attendees at University of British Columbia view Hitomi Kamanaka’s stunning documentary "Little Voices from Fukushima”. I organized Kama’s May 2019 visit to University of British Columbia for this screening in collaboration with MV Ramana of the Liu Institute for Global Studies, with support from the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, the Department of History, the Department of Political Science, the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability, the Faculty of Arts, the Department of Asian Studies, and the Centre for Japanese Research.

Article by 4 Corners journalist and artist Sonja Horoshko, published in the Four Corners Free Press, on a joint art opening of works by renowned artist Ed Singer and a book event featuring Downwind, held in Cortez Colorado in May 2019. Learn more about Ed’s incredible work here. Sonja has published numerous pieces about the legacies of uranium in the Four Corners region; read more of her work here.

The Rio Puerco River in New Mexico, in 1979 the site of the largest accidental release of radiation in United States history (roughly 3 times as much radiation was released in this accident at a uranium tailings pond as was released in the notorious Three Mile Island Nuclear power plant disaster that same year). It spilled 94 million gallons of radioactive water onto the Navajo Nation, impacting drinking water, livestock, and families across the region. Learn more.

Artist Jerrel Singer’s mural near Grey Mountain, Arizona on the lands of the Navajo Nation, featuring the words of Santee Dakota activist John Trudell: “Are they not waging nuclear war when the miners die from cancer from mining the uranium?” Read more about Jerrel’s work and follow him here!

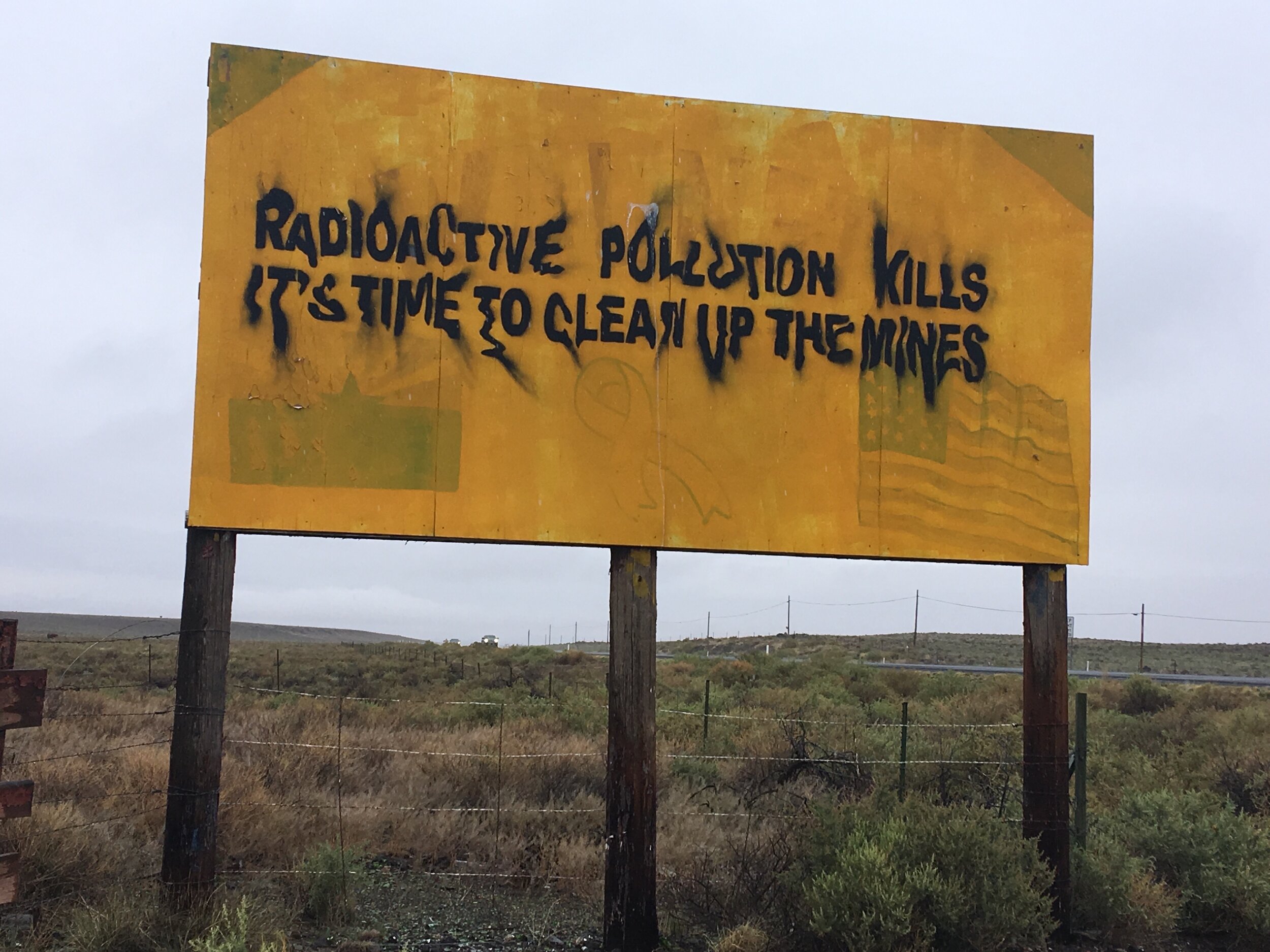

“Radioactive Pollution Kills: Its Time to Clean Up The Mines,” installation by artist @jetsonorama. Learn more about his work here.

Map from National Cancer Institute Study of thyroid cancer related to Iodine-131 dispersed by atmospheric nuclear testing in Nevada 1951-1962. View the study here.

Eugene, Oregon community reading of “Exposed,” a play by Utah downwinder Mary Dickson, held in commemoration of the 2018 anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This event was organized by Oregon WAND (Women’s Action for New Directions). Learn more about Mary’s play and WAND.

“#waterislife #goldminespill #noDAPL #WaterisSacred” Street art/Mural in Shiprock, New Mexico. Navajo Nation. Artist unknown. (If you know the artist please contact me at sarahalisabethfox@gmail.com!)